19th Century

Images: Barts Health NHS Trust Archives

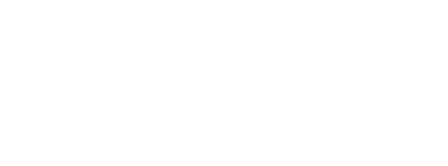

1815: John Abernethy and the development of a curriculum

Abernethy took up the mantle of Edward Nourse in the delivery of lectures, developing them into a more comprehensive course. These were so popular that the otherwise unrecognized student body began to swell. As a consequence of these lectures, a lecture theatre was built in 1791. He was elected as Principal Surgeon to the hospital in 1815. He was more renowned as a teacher than for his surgical skill, although he has a treatment for aneurysm named after him.

It is fair to say that he had an air of arrogance that did not endear him to all, most prominently the Crown and he lost his Royal Appointment to George IV after refusing to attend the King’s bedside until after he had completed giving his lecture at Barts. In 1822, he persuaded the hospital Governors to give formal recognition to the medical school, which had been gradually establishing itself during the late eighteenth century. He resigned in 1827, dying four years later.

1816: John Painter Vincent

Vincent was one of the last Members admitted by the Company of Surgeons in 1800. Two days after gaining his entry, The College Charter was granted and Vincent was again examined to become a member of The Royal College of Surgeons. (essentially speaking, exactly the same professional body!) He became Surgeon at Barts in 1816, was President of The Royal College of Surgeons in 1832 and 1840 and left his post at Barts in 1847 to become a Governor. James Paget later remembered him “as a very practical surgeon, shrewd in diagnosis and always prudent and watchful, but apparently shy and reserved and not at all given to teaching even in the wards. He never taught in the school – never even, I think, gave a clinical lecture.”

1822: Approval for Medical Training

After many years of providing medical training to physicians and surgeons alike, the Governors finally approved the provision of medical education within the hospital in 1822, thanks to the support of John Abernethy.

1824: William Lawrence

Lawrence was an apprentice to Abernethy and was made his Demonstrator when Abernethy became Lecturer on Anatomy in 1801. Later, Lawrence was elected Assistant Surgeon to the hospital but continued his training at The London Infirmary for Diseases of the Eye, returning to Barts a full Surgeon in 1824 where he remained for over forty years, succeeding Abernethy as Lecturer on Surgery in 1829. His absence from Barts may have been maintained by the serious disagreement between him and Abernethy over his exposition of Hunter’s Theory of Life. Specifically, in his lectures on The Natural History of Man (1819) he caused outrage by suggesting that the early chapters of Genesis were inconsistent with biological fact. Abernethy accused Lawrence of “perverting the honourable office entrusted to him by the College of Surgeons to the unworthy design of propagating opinions detrimental to society…”

James Paget had attended his lectures and later criticised himself for not having held them in sufficient esteem as a student, later recognising Lawrence’s style as the best ‘manner of scientific speaking’. He served as President of The Royal College of Surgeons in 1834 and 1865, and became Serjeant-Surgeon to Queen Victoria in 1858. He remains best remembered for continuing the tradition of Abernethy in the development of the medical school and for his influence on Paget and Harrison Cripps.

1825: Demolition of the medieval church of St Bartholomew-the-less

The church that had presided over the patients of the hospital from within its walls since the 12th Century was demolished and rebuilt, with only the original 12th Century tower remaining. This tower still stands and contains a peal of three bells that date to the 15th Century.

1834: Dead Criminals

In 1834, the still youthful Royal College of Surgeons purchased a house in Cock Lane, directly opposite the hospital, and gained a license for the dissection of hanged criminals. The proximity to Barts ensured the hospital’s continued importance in the training of surgeons in London.

1845: A Medical College at last!

Although training for physicians and surgeons and been present since its foundation, it was not until the 17th Century that medical students were first recorded and only in 1822 was medical training formally recognised. It took a further 23 years for The Medical College of St Bartholomew’s Hospital to be formally established.

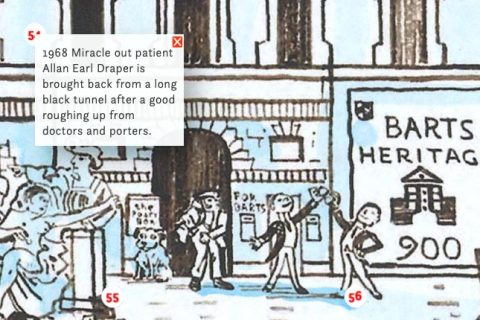

1847: James Paget

Born in 1814, it was as a naval career that first attracted the attention of James Paget. His father encouraged him in this and he set about studying maths, geometry and navigation. His mother burned the letter that his father wrote to a family friend, requesting that he take on young James as an apprentice seamen. Although distraught by his mother’s actions at the time, he later remarked on his teenaged choice of career as a “very silly wish of mine”.

At the age of 16, he decided that a surgical career would better suit his temperament and he was apprenticed to Charles Costerton, a surgeon-apothecary in his home town of Great Yarmouth. He spent four years there, learning the day-to-day duties of a doctor, including the invaluable experience of a cholera outbreak. Following his years as an apprentice, he was entered as an apprentice at Barts in 1834. During a post mortem examination he noticed small particles that were attached to muscle fibres, something commonly seen and remarked upon at autopsy at the time. He discovered was that these were cysts caused by the larvae of Trichenella worms that entered the body through eating unfresh or uncooked pork – a significant discovery in public health. Despite his success as a student, he did not fare so well as a qualified practitioner. With few patients to his name, he filled his time with teaching students, and cataloguing the contents of the Pathology Museum at Barts, becoming Curator of The Pathology Museum in 1837. In 1843, he was appointed Lecturer in Physiology at The Hospital. A year later he was appointed the first Warden of the first residential Hall of the Hospital. But it was not until 1847 that he was finally appointed as a surgeon at Barts. With this, his experience and skill again improved, and in 1858, he was made Serjent-Surgeon in Extraordinary to Queen Victoria and Surgeon-in-Ordinary to Albert Edward, Prince of Wales in 1868. He resigned from the hospital in 1871 due to ill health. His private practice continued and he remain in service to The Queen. He died in 1899 and at his funeral at Westminster Abbey, he had a Guard of Honour, formed of medical students from Barts. During his career, he was President of The Royal College of Surgeons, President of The Pathological society of London, President of The Clinical Society of London and received an honorary degree from Cambridge University. He is now considered to be one of the founding fathers of scientific medical pathology.

1850: Elizabeth Blackwell

Elizabeth Blackwell, one of the pioneers of medicine as a career for women, was permitted to study at Barts by James Paget. After Blackwell’s departure female students were again opposed and excluded until 1947.

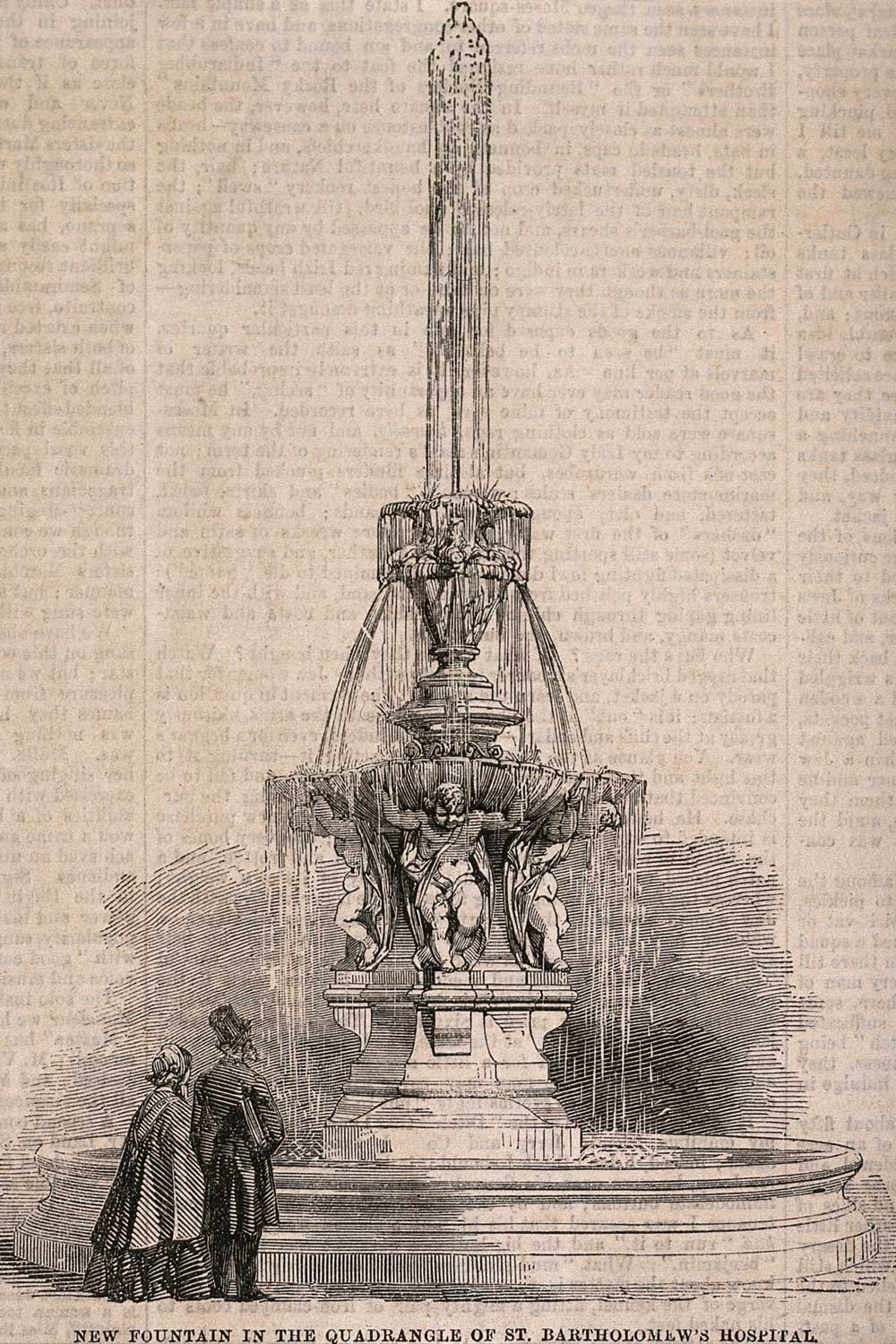

1859: The Fountain

The fountain at the centre of the square originally formed by the Gibbs blocks was a late addition to the hospital. It has nevertheless become an icon for the hospital and is frequently used to represent it and its alumni – including a dining club that was set up in 1919 and continues to run to this day (The Fountain Club).

1870: Henry Power

In October, 1844, Power entered St Bartholomew’s Hospital as a student. After practising at The Westminster Ophthalmic Hospital, he returned to Barts in 1870 and was appointed to the newly made post of Ophthalmic Surgeon. He was an original member of the Ophthalmological Society of the United Kingdom and was made Vice-President of The Royal College of Surgeons in 1885. His influences were felt beyond the world of surgery and he was Professor of Physiology at the Royal Veterinary College from 1881-1904 as well as President of the Society for employing the blind as masseurs, Surgeon to the Linen and Woollen Drapers’ Benevolent Fund and to the Artists’ Benevolent Fund. He was a talented painter in water-colours and made many drawings of the interesting cases that he saw at the Westminster Ophthalmic Hospital.

1876: Thomas Lauder Brunton

Whilst still a student at Edinburgh, Brunton won a gold medal for his thesis on digitalis and it was in the vein of pharmacology that he remained successful whilst working at Barts. He was an early advocate of the use of amyl nitrite to treat angina and wrote widely on the subject of clinical pharmacology.

1878: Schola Medicinae Sancti Bartholomei MDCCCLXXVIII

The Medical School Building with its latin inscription was completed in 1878.

1880: Henry Trentham Butlin

A pioneer of HNs assistant surgeon, Butlin was placed in charge of the Outpatient Department for Diseases of the Throat upon the resignation of Thomas Lauder Brunton. Although he never claimed to be a throat specialist, it was here that he made his name as a pioneer of head and neck surgery and along with Felix Semon and de Havilland Hall he was a principal founder of the Laryngological Society, which is now a section of the Royal Society of Medicine. In 1902, he was elected Consulting Surgeon and a Governor of The Hospital. He was placed on the Visiting Governors Committee in 1909. A ward at Barts is named in his memory.

1881-87: Nurse Number One

Having begun her training at the age of 21 in Nottingham and then Manchester, Ethel Gordon Manson’s expertise became sought-after and she came to London, working at our now sister hospital, The London Hospital in Whitechapel and then in Richmond. In 1881, she was appointed to Matron at Barts, a post that she held until 1887, only relinquishing it in order to marry Dr Bedford Fenwick. It is in her married name that she is perhaps better remembered as it was as Mrs Bedford Fenwick that her influence was truly felt. She was one of the founders of the Florence Nightingale Foundation and became the President of the International Council of Nurses for its first five years. She extended the period of time necessary for training as a nurse, and campaigned for their state registration. In short, she generated an understanding of nursing as a profession in its own right, akin to that of a physician or surgeon. She achieved her ambition and in 1919, The Nurses Registration Act was passed. In 1923, registration began and on this register Mrs Bedford Fenwick was, and to many always will be, Nurse No.1.

1882: William Harrison Cripps

Having studied at Barts, Cripps remained there as a graduate, initially as house surgeon and ultimately as elected Assistant Surgeon in 1882. He made his name in rectal surgery, and was an advocate for the use of inguinal colostomy for both treatment and palliation. He was a keen teacher with a cynical manner, known for his quick wit. He did not abide by the Listerian techniques of the day, such as operating under the carbolic spray in common use at the time. However, he was the only surgeon at the hospital at the time to make a complete change of clothing before surgery. He retired in 1909, becoming a Governor of the hospital and served as Vice-President to the Royal College of Surgeons from 1918-19.

1887-1910: Matron Stewart

Isla Stewart was Nightingale probationer at St Thomas’ Hospital in South London but was priveledged in being appointed to follow in the footsteps of Mrs Bedford Fenwick. Another formidable woman, she had forthright views on the future of nursing and continued the work that her predecessor had started. She made it it compulsory for probationers to be trained in basic nursing practice for the first six months, rather than attend lectures on medical and surgical nursing. These changes were instituted in 1894 and remained in place for the next twelve years, during which she lobbied for additional changes to the curriculum, including lectures by the then lecturer in pathology, Frederick William Andrewes, on the importance of aseptic techniques in surgery and surgical nursing.

In 1899, she co-authored of the first textbook on nursing, ‘Practical Nursing‘. She added to this with a further volume that described individual diseases and the practical nursing of these cases one by one. She was working on the third volume at the time of her death. The book’s completion fell to the assistant Matron at Barts, Miss Cutler and it was published in 1911.

Of Barts, she had said,“There is something about St Bartholomew’s Hospital, something – it may be in its age, its history or its associations – which creates towards it and, in its strength, a unique feeling among its members.”

It was on the strength of this sentiment that in 1899, she formed The League of St Bartholomew’s Nurses, of which she was president until 1908. The League, as it is affectionately known, is still active today.

Stewart was also a founder member of the Royal British Nurses Association, founder and first President of the Matrons Council, President of the Society for the State Registration of Trained Nurses, a member of the nursing board to Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service and Principal Matron to the Territorial Force Nursing Service.

1887: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s ‘A Study in Scarlet’

Sherlock Holmes, whilst using the laboratories at the hospital is introduced to Dr Watson, an alumnus of the Medical College. Fictional, of course, but important nonetheless! The most recent incarnation of Holmes on the BBC, saw Benedict Cumberbatch as the title role, throw himself from the roof of the hospital.

1896: X-rays

X-rays were first used at St Bartholomew’s. In 1896, the acquisition of an image that today would take 21 milliseconds would have required a 90-minute examination and delivered 15,000 times the amount of radiation. As a consequence, the operators of these machines often experienced radiation burns.

1897-1927: Frederick William Andrewes

Frederick Andrewes graduated from Christ Church, Oxford, before starting his clinical training at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in 1885. After a brief foray to The Royal Free Hospital he returned to Barts to study pathology and bacteriology, and in 1897 became lecturer on pathology, and pathologist at St Bartholomew’s. His legacy was original research on the classification of streptococci, the histology of lymphadenoma, and the problems of immunity. A ward at Barts is named in his memory.

Share…